According to Ducker Worldwide, a research firm that advises steel and aluminum producers, aluminum accounts for 11 percent of the weight of a variety of mass market cars, including the 2013 Chevrolet Malibu ECO.

The federal government's quest to double the average car's fuel economy by 2025 has intensified the long-running battle between steel and aluminum producers over one of their biggest customers.

Both industries are pouring millions of dollars into new mills capable of making the lighter, stronger metals needed to take 400 pounds -- about 10 percent -- out of the average car. That's the weight reduction needed to meet the proposed fleet standard of 54.5 miles per gallon, according to Ducker Worldwide, a research firm that advises steel and aluminum producers.

The drive for lighter vehicles has helped aluminum to make steady inroads into what is the steel industry's second biggest customer.

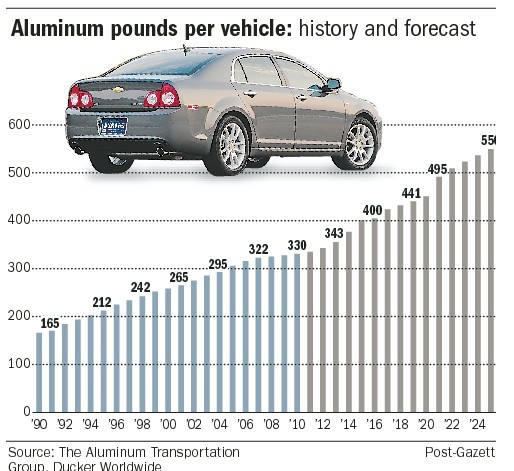

About 30 percent of car hoods and 20 percent of bumper beams are aluminum, according to Ducker. The consultant forecasts greater strides for the metal in the years ahead. It estimates the average North American vehicle will contain 550 pounds of aluminum by 2025, up from 343 pounds in 2012.

If that scenario plays out, aluminum will account for 16 percent of the weight of a light vehicle, about double the current aluminum content of the same kind of car, Ducker said. Steel's share will drop from 58 to 46 percent, the research firm said.

"It's good news for the aluminum industry. It's not any kind of death knell for the steel guys," said Ducker's Richard Schultz, who managed Alcoa's worldwide automotive business in the 1990s. "Vehicles will still be predominantly steel 20 years from now."

To a great extent, the competition has been a matter of aluminum's cost vs. steel's weight.

Aluminum cut its teeth in the auto business in the 1990s, loading up Audis and other luxury cars with aluminum components. The bigger the price tag, the easier it was to hide aluminum's price disadvantage.

Rising gasoline prices and aluminum's lighter weight have helped the industry muscle its way deeper into the automotive market. Ducker found that aluminum accounts for 11 percent of the weight of a variety of mass market cars: from Chevrolet's Malibu and Honda's Accord to luxury models such as the Lincoln MKZ and Mercedes-Benz's ML sports utility vehicle.

"We've got physics on our side at the end of the day. We can build a lighter car than steel can," said Alcoa's Randall Scheps, who heads the aluminum industry's Aluminum Transportation Group.

Steelmakers take the threat seriously, but say they have an advantage because they have been the automotive industry's partner from day one.

"We have, in my opinion, a very strong advantage in that regard," said Michael S. Williams, who directs U.S. Steel's North American sheet operations.

By the steel industry's calculations, the steel content of cars actually notched up in recent years from 63 percent to 65 percent.

"We've not lost. We've gained," said Lawrence Kavanagh of the Steel Market Development Institute, an industry-funded group.

Mr. Kavanagh believes that steel will remain the dominant automotive metal, saying it costs less to produce than aluminum and offers automakers lower manufacturing costs.

He also cites environmental advantages. When it comes to the emissions generated by making both metals and keeping cars that use them on the road, steel produces 5 to 20 percent less emissions than aluminum, he said.

Global steelmakers have invested $80 million since the late 1990s to develop designs for lightweight steel vehicles. They unveiled a prototype for a Future Steel Vehicle in May that will reduce the weight of auto bodies by 35 percent for a car powered by an electric battery.

"We can compete within a few percentage points of the mass reduction aluminum achieves today," said Ronald Krupitzer, vice president of the steel market development group.

No matter how light either material gets, both industries realize they must work closely with carmakers to provide metals that can be used to efficiently design and produce lighter weight cars.

"It's really the design and engineering of the product that we have to be closely tied to," Mr. Williams said.

U.S. Steel and its joint venture partner, Kobe Steel of Japan, are investing $400 million in a new steel processing line at their plant in Leipsic, Ohio. The equipment will alternately heat and cool advanced steel sheet to give it the strength and flexibility needed to shape it into automotive components. Mr. Williams said the new equipment, capable of producing 500,000 tons annually, will go into production in early 2013.

Russian steelmaker OAO Severstal is revamping its Dearborn, Mich., plant to produce the next generation of automotive steels, a project financed by a $730 million loan from the U.S. Department of Energy.

On the aluminum front, Alcoa announced plans last month to invest $300 million to enable its Davenport, Iowa, works to keep up with automotive demand. The decision was based on business already on the books, but Alcoa expects growth beyond that.

"These are long-term decisions. These are assets that are going to be in place for 50 years," said Mr. Scheps, who worked with the auto industry before joining Alcoa six years ago.

Novelis is investing $200 million to boost production of aluminum automotive sheet at its Oswego, N.Y., plant, citing growing demand from its customers.

Analyst Charles Bradford has covered competition between the two industries for decades. He witnessed aluminum's wholesale capture of the beverage can market and saw steel maintain its stronghold on food cans.

But when it comes to cars, the New York analyst believes that the handwriting is on the wall.

"Aluminum has gained market share every year," Mr. Bradford said. "Steel has to be the loser in terms of pounds. It doesn't have to be the loser in terms of profit."

He said the challenge for steelmakers will be to command higher profit margins on the next generation of steels than the industry realized from the lower grade of steels they will replace.

"They may be able to make more money if they sell less pounds. That's going to be the trick," Mr. Bradford said.